The far north west of Australia showcases some of the most remote and rugged terrain on Earth, characterised by the stunning ranges and gorges of the Kimberley and Pilbara.

Its coastline and marine life are equally spectacular.

And the pristine waters stretching from Exmouth Gulf around to the Northern Territory (NT) constitutes the world’s most significant wild harvest pearl fishery, for this is home for the Pinctada maxima or silver-lipped pearl oyster.

Global best practice

The MSC blue label is the consumers' guarantee that the fishery has been positively assessed by a third party (independent of the MSC) on a robust set of global best practice sustainability standards.

This fishery is the first of its kind to be certified, extending the principle of sustainability from harvesting seafood to harvesting pearl oysters and their pearls for jewellery. It means that lovers of fine pearls can not only look good but feel good, knowing they’re helping do the right thing by marine life.

The cultured pearls grown in P. maxima in Australia are called South Sea pearls with the Paspaley Group being the oldest and biggest producer in Australia.

A family-owned company, its links with WA go back to 1919 when the Paspaley family migrated from Greece. Soon after, they became deeply involved in pearling.

In 1932, Nicholas Paspaley, then just 19, was at the helm of his own pearling lugger. Not long after he found a large natural pearl that turned out to be three times the value of his lugger. He later founded the Paspaley Pearling Company.

“Ever since I can remember, pearling has always been the primary topic of conversation in the family.”

Mr Paspaley describes MSC accreditation as the paramount recognition of environmental integrity.

“We are delighted to have achieved this important milestone,” he says. "Sustainable production is part of our DNA and we have in fact been operating this way for much longer than it has been fashionable."

“It is how we do what we do and there is no other way. We work hard to harmonise with our environment, we are innovative and creative, and we are proud of our environmental credentials.”

To achieve the MSC standard, the fishery was assessed on three demonstrable principles: sustainable stock; impact on the marine environment; and sound management of the fishery.

Certification took two years, but that represents a mere drop in the Indian Ocean set against the origins of this fishery.

The importance of sustainability and environmental stewardship

Melanie Carrington, a director of the Maxima Pearling Company, and one of the very few Japanese-trained Australian Pearl Technicians, understands the rarity of an Australian South Sea pearl.

“A wild collected P. maxima pearl oyster must be carefully reared for at least two years in the clean, nutrient rich North-Western Australian waters before it can produce a pearl.”

“We look to harvest half the seeded shell every two years and nowadays maybe up to 90% have pearls inside,” says Ms Carrington. “Just over half of the pearls harvested will be of sufficient quality.”

Mr Brown says Australians should be proud that their cultured pearl industry has been certified as sustainable, and have confidence that the fishery is being looked after.

“The discerning customer is usually well informed about sustainable credentials, so this certification is something the Australian public can be quite proud of.”

Aaron Irving, chief executive of the Pearl Producers Association, also points to the benefits of the ecolabel.

“MSC certification assists customers in making an ethical choice – a choice that celebrates careful management and marine stewardship, a choice they can make because the MSC ecolabel communicates to customers that the certified fishery has been assessed according to a robust set of global best practice sustainability standards that are second to none,” Mr Irving explains.

“It enables us to provide our customers with an added assurance that they are able to buy Australian South Sea pearls with confidence that their pearl has come from a carefully managed and sustainable source – that is cultured in harmony with the natural marine environment with almost zero effect."

“The Australian pearling industry and the WA and NT government fisheries departments have developed an excellent managed fishery quota system that has demonstrated over the decades that the wild shell harvest can be managed sustainably,” he says.

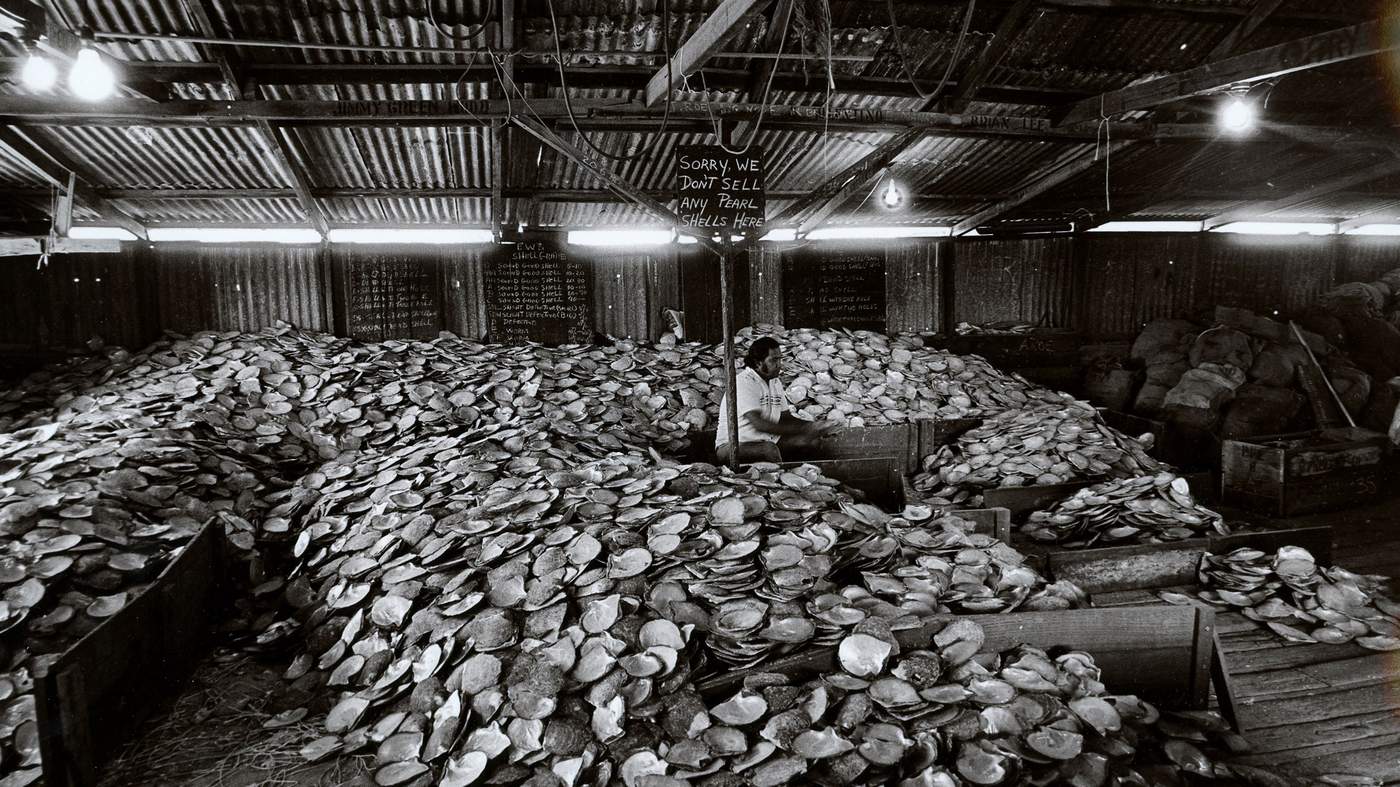

All images © Paspaley Pearling Company unless otherwise stated